| Hour

Ten

The

MG Lola was now running like clockwork, and the

car's pitstops were following a regular twelve-lap

schedule. Just before his first such stint came

to an end, Thomas Erdos passed the #30 Kruse Motorsport

Courage as it languished in the pits, elevating

the RML MG to 28th position. His stop, when it

came at 12:50am, was problem-free and routine,

and that allowed him to resume his challenge on

the #35 G-Force entry, catching and passing Gary

Pickering when the Londoner took to the pitlane

at ten past one.

Fifteen

minutes later and one of the team's predicted

rivals in this race, the #30 Kruse Courage, hit

more problems, with an off at the Dunlop Chicane

soon after returning to the track, further reducing

its challenge in LMP2. Tommy meanwhile, was closing

on the #89 Sebah Automotive Porsche and also,

now, the #32 Intersport Lola. The one-time LMP2

leader had been encountering a succession of minor

woes, but they seemed to be increasing in seriousness.

Taking the Lola's position at the head of the

class had been the the #37 Belmondo Courage, followed

soon afterwards for second by its sister car,

the #36.

When

Gregor Fisken took the Intersport Lola back into

the pits five minutes later, it handed 26th place

and a potential foothold on the third step of

the LMP2 podium to RML's MG Lola. Tantalisingly

close, just a lap and a half ahead, lay the #36

Courage, but overall status was nearer at hand.

Erdos duly passed the Sebah Porsche, depriving

Dane Thorkild Thyrring of 25th place and setting

the #25 MG Lola in his stead.

At

half-past one Tommy's triple stint came to an

end, but what should have been another routine

and trouble-free handover to Mike Newton turned

out to be anything but. For no obvious reason

the electrics failed to revive when it came time

for Mike to drive out of the box. There was much

shaking of heads. There is nothing more frustrating

that an intermittent fault that proves so elusive

to track down. Once again, as had happened several

times before, the MG was dragged backwards into

the pit so that the whole cohort of engineers

and mechanics could set to work on the car. Outside

on the pit apron, only four personnel are permitted

to work on a car. Once inside the garage, any

number of people can be called upon to assist.

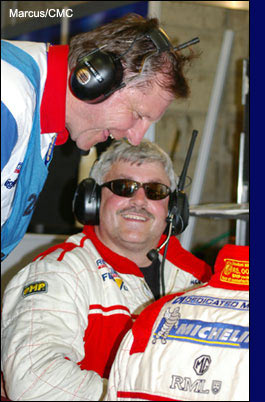

The

pause gave us a chance to catch up with the Brazilian,

and discover how his late-night run had gone.

"It went really well," he said, sounding

tired, but clearly exhilarated by having continued

Warren's fight-back so successfully. "It

was hard work. Early in my first stint, I lost

the paddle-shift, so I had to use the manual gearchange

from then on. That also meant reverting to right-foot

braking, which I've not had to do for a while."

His observations of the track conditions were

not exactly favourable, but concurred with the

feedback being received from other drivers. "It

was very, very slippery out there. There's just

so much cement dust, possibly too much, and it

has made parts of the track exceedingly slippy.

Thankfully, the tyres have been so good. They

just stay, stay, stay. Through the Porsche Curves,

and at Indianapolis, the car felt so stable, it

was fantastic." Casting concerned glances

to the garage from time to time, it was clear

that he was distressed to see much of his hard

work going for nothing. "This is all so frustrating,"

he shrugged. "All that work, and to regain

P3, and then this. I can't believe it." Alastair

Mcqueen agreed. "It was all going so well,"

he said. The

pause gave us a chance to catch up with the Brazilian,

and discover how his late-night run had gone.

"It went really well," he said, sounding

tired, but clearly exhilarated by having continued

Warren's fight-back so successfully. "It

was hard work. Early in my first stint, I lost

the paddle-shift, so I had to use the manual gearchange

from then on. That also meant reverting to right-foot

braking, which I've not had to do for a while."

His observations of the track conditions were

not exactly favourable, but concurred with the

feedback being received from other drivers. "It

was very, very slippery out there. There's just

so much cement dust, possibly too much, and it

has made parts of the track exceedingly slippy.

Thankfully, the tyres have been so good. They

just stay, stay, stay. Through the Porsche Curves,

and at Indianapolis, the car felt so stable, it

was fantastic." Casting concerned glances

to the garage from time to time, it was clear

that he was distressed to see much of his hard

work going for nothing. "This is all so frustrating,"

he shrugged. "All that work, and to regain

P3, and then this. I can't believe it." Alastair

Mcqueen agreed. "It was all going so well,"

he said.

Back to

top

Hour

Eleven

The

stoppage ended up at being almost half an hour

in length, and Mike was not back out and circulating

until just before two o'clock. The delay had dropped

the team to 26th place overall, with the Sebah

Porsche back in front once again, this time by

several laps. Mike's times, however, were far

more encouraging. Although some way short of his

earlier bests - well, this was the middle of the

night, after all, and he was driving on the manual

gearchange - they were still markedly quicker

than those of his rivals ahead.

Hours

Twelve & Thirteen

The

remainder of this stint progressed without incident,

and Mike completed a refuelling pitstop at ten

to three without the feared electrical gremlin

rearing its head. Others were not so fortunate.

On the hour the #37 Courage hit a problem that

forced Belmondo to haul the car into the garage,

allowing Mike Newton to close to within less than

two laps, but he'd not have the chance to get

any closer. His next scheduled stop came up at

3:38, with the CEO of AD Group handing over driving

duties to Warren Hughes. Thankfully the car fired

up again without hesitation, and it was a matter

of moments before Hughes was roaring back out

along the pit exit. He soon found that same groove

that had served him so well earlier in the night,

and was posting times in the low three-fifties.

Rounding

off the twelfth hour of the race, and seeing the

RML MG Lola through to half distance, Warren Hughes

enjoyed a stress-free run well past four o'clock

and down to half-past. Just before his next scheduled

stop he posted one of his best laps of the race,

a 3:49.524, and by doing so carried the MG Lola

through to 25th place overall, passing the #37

Courage and making a first claim on second position

in LMP2. The class leader at the time was young

Adam Sharpe in the #36 car, a mere three laps

ahead.

Back to

top

Hour

Fourteen

Frustratingly,

it was all just a temporary elevation. The pitstop

when it came did not go smoothly, and after refuelling

the car, the car was trolleyed backwards into

the garage. Sure enough, four minutes later the

#37 Belmondo car wailed up the tribune canyon

to snatch back second in class and started to

pull out a meaningful lead. It would be a full

24 minutes in the garage for Warren before Phil

Barker waved him out and on his way once more,

this time with some tempting soft-compound rubber

on all four corners. The fickle finger of fate

was pointing both ways through this summer's night,

however, and both Belmondo cars would be serving

time in the garage before the race was another

hour older. The #37 was first to pit at two minutes

to five, followed moments later by the #36. First

in would be first out, just five minutes later,

but the #37 would languish for some time yet.

At five eighteen Hughes sailed serenely by, and

then rubbed salt into the wound by posting his

fastest lap of the race, not once, but three times.

His first improvement; 3:47.875, was followed

two laps later by an even quicker 3:47.649, and

then rounded off by a scintillating 3:47.601.

Hour

Fifteen

There

must have been a collective sigh of relief from

the RML garage when Warren completed a perfect

pitstop at five-forty. He was stationary for just

five minutes, and then rapidly back out on track

and lapping in the mid 3:50's or 53's, establishing

a firm grip on 24th place overall, second in LMP2.

The car had covered 178 laps of the 13.6 kilometer

Circuit du Sarthe.

The

team's next target was the Luc Alphand Porsche,

being piloted by Jerome Policand, four laps ahead.

Passing the #72 entry would not happen for a while,

and not while Warren was in the car. At just after

half-six he would hand over the MG to Thomas Erdos,

and once again, the dice would tumble favourably.

It was a straightforward and reassuringly rapid

pitstop that saw Erdos heading back into the fray

with barely a heartbeat missed. "We've just

got to try and keep this thing going," said

Warren. Another with similar views was Scot Allan

McNish, barging headlong into the tyrewall at

Indianapolis when a tyre failed on his Audi R8.

He got it back to the pits and the car was racing

again inside ten minutes. Not so Xavier Pompidou

in the T2M Porsche, suffering a massive impact

at the same corner. That car wouldn't be moving

again - ever - although Xavier was amazingly unscathed.

Back to

top

Hour

Sixteen

Thomas

Erdos marked the start of the sixteenth hour by

passing the #89 Sebah Porsche, static in the pits,

at five past seven. It was another notch on the

overall order, but far more important was the

next LMP2 place. That was still held by the #36

Belmondo Courage, and by twenty-past the margin

stood at less than two laps with Erdos closing

at a rate of fifteen or twenty seconds each lap.

In the opposite direction, he had a similar two-lap

cushion over the #37, but was adding comfort by

outpacing the second Belmondo car by 30 seconds

or more.

The

next scheduled pitstop came round at 7:33. Fingers

crossed, it went without a hitch. Slick and fast

and totally faultless, the car was dosed up with

fuel and Tommy sent on his way. "I hope we

finish. I really hope we do," said one of

the mechanics. This wasn't a plea; this was grim

determination.

Back to

top

Hours

Seventeen and Eighteen

The

battle in LMP2 has been fought as much in the

garages as on the track. Not one of the remaining

significant runners has enjoyed an easy passage,

and the #36 car was about to encounter another

patch of rough water. A conventional stop at ten

past eight was followed quarter of an hour later

by an unscheduled sojourn in the garage that would

last long enough to allow Tommy an unopposed claim

on 22nd overall. Bringing a far bigger cheer to

the RML garage, however, was the realisation that

this meant that the MG was now leading the class

for the first time. Sixteen hours previously such

an achievement might have seemed unlikely, but

a potent mix of perseverance, skill and mutual

encouragement can work wonders.

With

another faultless pitstop the prospects were suddenly

looking far more encouraging, and Erdos pressed

on confidently for another half hour. He passing

the #72 Luc Alphand Porsche just before the hour,

and then completed his stint by handing the MG

back to Mike Newton at 9:08. Not only was Mike

entrusted with the next stint, but he also had

the personal pleasure of knowing that his car

was now leading its class at Le Mans. It must

have been a very special sensation, made easier

to bear by the knowledge that he had a three-lap

lead over the #37 and four over the #36. Regrettably,

it was not going to last. At half past nine Mike

was back down the pitlane, and it wasn't a scheduled

stop. The car was barely at rest before the engine

cover was off. It didn't take a detailed examination

to confirm the problem. "We've got a gearbox

oil leak," acknowledged Ray Mallock. "One

of the castings may be cracked, so we're seeing

if we can fix it." Proof that this was the

culprit came from Jamie Campbell-Walter, who had

been following the MG when the fracture occurred.

He caught the oil and slid into the barriers at

the first Mulsanne chicane.

It

was desperately sad to see all that hard work

slipping through the team's proverbial fingers.

The Luc Alphand Porsche was the first to take

advantage, moving through to regain 21st place

at 9:40. Eight minutes later the #37 Courage reclaimed

the class lead, and then the #36 knocked the MG

down to third.

Back to

top

Hour

Nineteen

With

the car stationary in the garage the team’s

position on those podium steps was looking increasingly

fragile, and as the clock ticked past ten o’clock

the timing screens already confirmed that 25th

overall was third in LMP2, yet the likelihood

of slipping to fourth was imminent. The #30 Kruse

Courage, long since overtaken, was back up to

pace and only a few laps adrift.

As

it must always be throughout the story of this

race, all credit to the RML mechanics and engineers,

who completed the repair in record time. Weary

to the bone they may have been, but they never

wavered, and their efforts had Mike back out onto

the circuit and racing again by quarter past ten.

It was a close call. Tim Mullen in the Kruse entry

had moved ahead of the MG on the previous lap,

but had just arrived in the pitlane himself for

a lengthy, if scheduled, stop. It was a matter

if just a single lap of the track before Mike

had restored RML to that bottom step once more

and the road to recovery could be resumed.

Having

achieved so much, it really was starting to feel

like one step forward and two back. From the class

lead, Mike now faced a six-lap deficit on just

the first of the two Belmondos, yet he couldn’t

begin the task of reducing that margin just yet.

He was passing through the pitlane again after

a couple of laps for fuel, a full set of tyres

and, more importantly, a quick check-up of the

repair to make sure that everything was as it

should be. Passed fit for duty, the MG was soon

on its way.

Hour

Twenty

The

next half hour or so proved routinely uneventful

– something of a relief perhaps. Mike notched

into a rhythm of four-minute laps and that consolidated

the car’s position, and meant that Warren

was perfectly placed to take the fight back to

Team Belmondo when he clambered aboard for his

next double-stint at 11:12. The #36 had lost twenty

minutes in the pits just before the hour, so the

gap was down to spitting distance. Indeed, when

Mullen pitted at quarter past, it meant that all

three – the #36, the RML #25, and the Kruse

#30, were all on the same lap. The difference

was the relative speeds, and that suggested an

advantage in Hughes’ favour of fifteen to

twenty seconds with every lap completed.

Sure

enough, by half past eleven the gap between the

tail of the #36 Belmondo and the MG’s nose

had been cut to less than a minute. By quarter-to

it was thirty seconds and every lap was bringing

them closer together. The retirement of the #17

Pescarolo, for so long a serious challenge and

French hope for the outright lead, went almost

un-noticed in the RML garage, because Hughes was

about to weave through the Ford chicane with that

red, white and blue nose tucked tight under the

rear wing of Adam Sharpe’s Courage. As they

crossed the line the gap was clocked at a mere

0.774 seconds, and as the noise from their engines

echoed between the grandstands, Hughes notched

the MG to the side and eased by. The second step

was RML’s once more.

Within

a lap Hughes had established a lead of fifteen

seconds. His times were all neatly bracketed around

the three-fifty-two mark, with a 3:51.930 following

a 3:52.937 following a 3:53.891. My midday, and

inside three laps, he’d moved clear of Sharpe

to the tune of 45 seconds.

Back

to top

Hours

Twenty-One and Twenty-Two

With

just under four hours to go – just?

That’s longer than most regular endurance

events! – Warren came in for a regular pitstop.

Five minutes later, so did Sharpe. They were shadowing

one another, but Warren’s shadow was lengthening

the quicker. He had continued to impose his dominance

over the young Briton in the French car, and the

gap had grown to more than a lap. In doing so,

Warren had also drawn closer to the #37, but the

margin was larger than he could hope to close

by raw speed and talent alone. By half past twelve

the MG Lola had covered 260 laps in total and

was lying 23rd overall, second in LMP2, but still

six laps adrift.

These

last hours before the chequered flag have a strange

detachment. There are crowds milling around the

stands and through the Village, but many are totally

oblivious of the action on the track. While the

cars continue to fly by just as fast as they ever

have, their drivers deep in concentration; hot

and tired, their arms and necks aching from the

constant strain and g-forces, it’s all too

easy to take them for granted. The bellow of a

passing car earns a casual glance, the pre-race

purity of its paintwork long since blemished by

an acne of dead flies, spent rubber and tank-tape,

but never underestimate the bravery of these guys.

Fuelled by adrenalin and determination, encouraged

by the support of seemingly tireless mechanics,

they push on regardless. It’s a humbling

thought. These

last hours before the chequered flag have a strange

detachment. There are crowds milling around the

stands and through the Village, but many are totally

oblivious of the action on the track. While the

cars continue to fly by just as fast as they ever

have, their drivers deep in concentration; hot

and tired, their arms and necks aching from the

constant strain and g-forces, it’s all too

easy to take them for granted. The bellow of a

passing car earns a casual glance, the pre-race

purity of its paintwork long since blemished by

an acne of dead flies, spent rubber and tank-tape,

but never underestimate the bravery of these guys.

Fuelled by adrenalin and determination, encouraged

by the support of seemingly tireless mechanics,

they push on regardless. It’s a humbling

thought.

Thomas

Erdos was about to become one such driver. At

five-to-one Warren Hughes’ final stint came

to an end as the soft-spoken Geordie handed over

responsibility for the last three hours to Tommy.

The first of those sixty minute batches was to

be pretty uneventful, with the RML MG moving smoothly

through to 22nd overall after passing the #89

Sebah Automotive Porsche – again

– and pulling three laps clear of the #36

Belmondo Courage. As the official electronic clock

on the Rolex gantry fluttered its digits over

to two-o’clock, the #37 Courage began its

289th lap, still with five laps in hand over the

chasing Erdos. I have a entry in my notebook that

simply states: ‘Only a miracle or a mistake

by the #37 can change the result’. Little

did I know what lay around the corner.

Hour Twenty-Three

The

corner in question turned out to be the Ford Chicane,

and the time was 2:07. As Tommy came onto the

brakes after negotiating the Porsche Curves, slowing

the car’s momentum into the first element,

misfortune cast her cards in equal measure. One

of the right rear suspension arms sheared from

its mounting, tipping the car into a series of

wild gyrations across kerb and gravel and coming

to rest just yards from the entrance to the pitlane.

“It snapped as soon as I went on the brakes,”

explained Erdos afterwards. “We were very

lucky that I didn’t hit anything, since

there was nothing I could do about it at all.”

Like a cruel test from the Gods, being so close

to the pits was a lifeline, but with less than

two hours remaining and with the #37 Belmondo

Courage already five laps clear and the #36 closing

fast, the result RML had started to dream of was

suddenly looking unlikely.

Back

in the garage there was a moment’s hesitation

as those watching the TV monitors gaped in disbelief

before instinct and training took over. Like ants

disturbed in their nest, red-suited RML personnel

were suddenly busying themselves for action. Tiredness

was wiped from their faces along with the sweat

as they hurried to take up the tasks they knew

were theirs. Phil Barker lived up to his name,

issuing commands with the minimum of words. While

others marvelled at the fact that the incident

had taken place at the very entrance to the pitlane,

four mechanics were already running towards the

car, Barker’s strict instructions not to

“cross the line” ringing in their

ears.

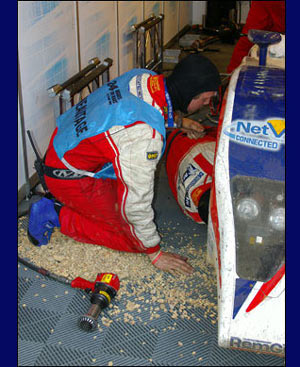

In

the end they weren’t needed. The marshals

had moved swiftly into action, and using one of

the Manitou recovery hoists, had pulled the MG

clear of the gravel and, as luck would have it,

hauled it towards the pit entry. Once on terra

firma Tommy was able to coax the car gently

back to the garage, crabbing slightly sideways

and with the right rear sunk low to the ground.

It was a desperately sorry sight, with the once

resplendent bodywork scarred not only by twenty-two

hours of hard racing, but now covered in the dust

and debris of a trip through the gravel. Every

available hand was on call to haul the car backwards

into the garage and then begin not only the repair

of the damaged suspension, but also the painstaking

removal of every last trace of the harsh sharp-edged

stone chippings used at Le Mans. It was a strangely

silent operation, the thunderous noise from the

racetrack as cars accelerated up the pit straight

drowning out and rendering useless any form of

speech inside the garage. It was superfluous anyway.

Save for a few shouted instructions from Barker,

his brigade knew the drill. It was impressive

to watch, and inspiring. There wasn’t a

single man amongst them that seemed to consider

for a moment that the race was over. After what

they’d already been through, their determination

was at once both staggering and admirable. In

the end they weren’t needed. The marshals

had moved swiftly into action, and using one of

the Manitou recovery hoists, had pulled the MG

clear of the gravel and, as luck would have it,

hauled it towards the pit entry. Once on terra

firma Tommy was able to coax the car gently

back to the garage, crabbing slightly sideways

and with the right rear sunk low to the ground.

It was a desperately sorry sight, with the once

resplendent bodywork scarred not only by twenty-two

hours of hard racing, but now covered in the dust

and debris of a trip through the gravel. Every

available hand was on call to haul the car backwards

into the garage and then begin not only the repair

of the damaged suspension, but also the painstaking

removal of every last trace of the harsh sharp-edged

stone chippings used at Le Mans. It was a strangely

silent operation, the thunderous noise from the

racetrack as cars accelerated up the pit straight

drowning out and rendering useless any form of

speech inside the garage. It was superfluous anyway.

Save for a few shouted instructions from Barker,

his brigade knew the drill. It was impressive

to watch, and inspiring. There wasn’t a

single man amongst them that seemed to consider

for a moment that the race was over. After what

they’d already been through, their determination

was at once both staggering and admirable.

Throughout

the next half-hour Erdos sat impassively. A fan

had been set on the sidepod of the car to blow

air into his visor, his movements deliberate and

his thoughts unreadable. “I was thinking,

what else can possible go wrong?” he admitted

afterwards. “I was tired. I’d done

two triple-stints, and then doubles, and at the

end was in the car for three hours. I felt emotionally

drained. I was also a little concerned, because

it was a very unusual failure. I was worried that

the other side might go the same way.”

Behind

him the action continued unabated. While the left

side of the car was being rebuilt, the right hand

side was being painstakingly inspected. What had

happened once could happen again, and even at

this late stage in the race, nobody was prepared

to take chances with the car or, more important,

the man inside it. Amazingly, despite what looked

to be a violently physical accident, the rest

of the car had survived almost unscathed, confirming

the resilience of carbon-fibre construction. Nobody

was taking any chances though, and every nut,

bolt and accessible component that could be examined

was checked for tightness or damage.

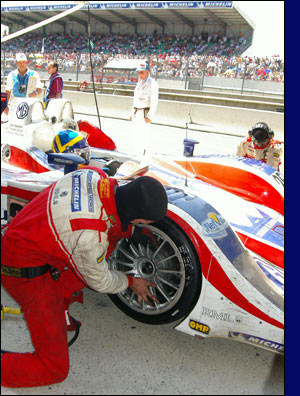

Amazingly,

within twenty minutes of arriving in the garage,

wheels were already going back on the EX264. They

glistened wetly as the bright lights reflected

off the smooth surface of the fresh rubber. Two

minutes later, the rear panel was being secured

in place over the engine and the car trolleyed

unceremoniously out of the garage, dumped on the

ground, and then raised on its jacks. Only then

were the race tyres fitted – pre-scrubbed

and ready for the track ahead. The team was taking

no chances, and had used the new tyres to wheel

the car across any remaining chippings on the

garage floor, saving the best for the track. Amazingly,

within twenty minutes of arriving in the garage,

wheels were already going back on the EX264. They

glistened wetly as the bright lights reflected

off the smooth surface of the fresh rubber. Two

minutes later, the rear panel was being secured

in place over the engine and the car trolleyed

unceremoniously out of the garage, dumped on the

ground, and then raised on its jacks. Only then

were the race tyres fitted – pre-scrubbed

and ready for the track ahead. The team was taking

no chances, and had used the new tyres to wheel

the car across any remaining chippings on the

garage floor, saving the best for the track.

At

two thirty-five, almost exactly thirty minutes

since he’d been lost to sight within a cloud

of dust at the Ford Chicane, Thomas Erdos barked

the MG Judd V8 into life and roared off up the

pitlane, leaving only the smallest trail of gravel.

It was a remarkable demonstration of determination,

bravery and skill, and only now did anyone turn

to the timing screens to see what the last hour

and a quarter offered. They were greeted by another

amazing twist in this already unbelievable tale:

not one, but both Belmondo Courages were also

in their garages. The leader, it was suggested,

had holed a piston, while the #36 was suffering

from an overheated starternator. “Those

are the very problems we always used to catch,”

said Mike Newton, referring to RML’s period

with the AER-engined EX257. Suddenly everyone

recognised that, despite the events of the previous

half-hour, and the considerable deficit the team

now faced, there was still a chance.

In

amongst all this had been a cruel coincidence.

The Aston Martin pitlane crew had occasionally

spilled over onto the RML box during the race,

when both their cars in the adjacent garage had

been expected close together. As the MG emerged

into the daylight after what must have looked

to many like a potential retirement, the refuelling

crew for the #58 had to step aside, but their

gaze didn’t waver. Peering over the MG and

her attendant personnel, they were scanning the

distant track for any sign of their car. Only

after the begrimed MG had hurtled away and the

noise of its departure faded into the distance

did they accept the stark reality that the DBR9

they were waiting for wouldn’t be coming

back. It had run out of fuel after more than twenty-two

hours. One can only begin to imagine their thoughts.

Back to

top

Finish

Meanwhile,

back in the RML garage, the team had one eye on

the screens, and another along the pitlane towards

the Belmondo garage. There was an air of high

tension, but Phil Barker suddenly had a skip in

his step as he ran across to the pitwall to consult

with Alastair Mcqueen. He, for one, knew the race

wasn’t over. Tommy had also discovered that

the car had survived this latest ordeal reasonably

well, and even if he couldn’t possibly match

the kind of pace he and Warren had demonstrated

earlier in the race, there was a good chance he

could overhaul the two Courages. Both had pulled

ahead in the class during the MG’s enforced

stop and were now several laps clear, albeit stationery.

Under

strict instructions over the radio that there

were to be “no heroics” Erdos eased

back and started lapping in the mid four-tens.

So long as the two Belmondo cars remained in their

garage he had no need to push, and the strategy

worked. At 2:42 he came through to begin his next

lap, and overtook the #36 for second in LMP2.

That left the #37 still several laps in front,

but with a damaged engine did it pose a threat?

Incredibly, it did! Having had it confirmed that

the mechanics were not doing any work on the car,

it was with some incredulity that those watching

the monitors suddenly caught sight of the #37

leaving the pitlane. There was a collective sigh

of relief, however, when the car’s pace,

and the accompanying pall of smoke, confirmed

that it was going nowhere fast, even if it did

have five laps in hand. Trailing smoke and travelling

at pitlane speed, or slower, the car was being

accompanied around the circuit by a Mexican wave

of white flags. Under

strict instructions over the radio that there

were to be “no heroics” Erdos eased

back and started lapping in the mid four-tens.

So long as the two Belmondo cars remained in their

garage he had no need to push, and the strategy

worked. At 2:42 he came through to begin his next

lap, and overtook the #36 for second in LMP2.

That left the #37 still several laps in front,

but with a damaged engine did it pose a threat?

Incredibly, it did! Having had it confirmed that

the mechanics were not doing any work on the car,

it was with some incredulity that those watching

the monitors suddenly caught sight of the #37

leaving the pitlane. There was a collective sigh

of relief, however, when the car’s pace,

and the accompanying pall of smoke, confirmed

that it was going nowhere fast, even if it did

have five laps in hand. Trailing smoke and travelling

at pitlane speed, or slower, the car was being

accompanied around the circuit by a Mexican wave

of white flags.

Minutes

later the #36 also rejoined the race. Adam Sharpe

was back in the cockpit, but with a three-lap

arrears he had a lot of ground to make up. He

set about the task with some zeal, and was actually

matching Tommy’s pace at this stage. The

Brazilian was intent on making sure that, having

recovered so much, RML’s position wasn’t

about to be endangered by overstressing the MG.

“The engine was fantastic throughout,”

enthused the Brazilian some while later. “It

never missed a beat, and it was strong from start

to finish, but I wasn’t about to make it

do any more than we truly needed.” There

had been times when the team had pushed very hard

to make up lost ground, but this was an occasion

where discretion was needed.

When

the Belmondo car finally stuttered to a halt near

Maison Blanche at just after three, hoping to

wait there until the final lap and then crawl

across the line almost an hour later, the seal

had been set. At three-fifteen Tommy swept passed

the stationary car, and began his next lap as

class leader. There was hardly anyone in the RML

pit who could quite believe what they had just

gone through, but it wasn’t over yet. The

final hour of the Le Mans marathon may seem like

the end of the race to the spectators, but it

is nonetheless another sixty-minutes of sprint

racing, and some races don’t even last as

long. A final scheduled pitstop saw the MG refuelled,

re-tyred and smoothly back into action again with

barely a minute’s pause. If only all the

car’s pitstops could have gone so well.

If

the challenge from the #37 had gone, the #36 Courage

was still in the chase. Tommy couldn’t afford

to ease back too much, and the 73rd running of

the Le Mans 24 Hours offered similar tension throughout.

In every class, there was a battle in progress

for the podium, with leaders and chasers each

within sight of the other. Not until the final

ten minutes did it appear that the protagonists

had accepted their fate, and while the overall

winners, two Audi R8s and the sole surviving Pescarolo

formed up to stage the perfect photo-finish, realisation

dawned upon the hot and weary faces around the

RML garage that the could actually win.

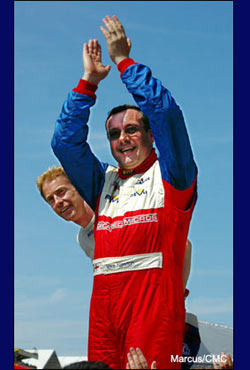

As

luck would have it – and didn’t it

always throughout this race? – Tommy was

ahead of the race leaders on the track, so the

finish had been staged for several minutes before

the glare of the MG’s headlights could be

seen glittering through the haze. It couldn’t

have worked better. With a flourish, the commentator

announced the arrival of the LMP2 winner. In solitary

splendour, and accompanied by an enormous cheer

from the crowd, the diminutive MG Lola EX264 wailed

its Judd-inspired battle-cry across the finish

line, Tommy pedalling the throttle into a crescendo

of defiance. Not only was he celebrating the finish

the team so much deserved; not just a podium,

but also that rare distinction, victory at Le

Mans. Mike Newton and Warren Hughes both climbed

high atop the pitwall to welcome home their car,

their feet swathed in the waving arms of a mass

of cheering and ecstatic team members, better

halves and sponsor’s guests. It was an enormously

emotional moment, and the relief that comes after

so many hours of strain and pressure was clear

for anyone to see. As

luck would have it – and didn’t it

always throughout this race? – Tommy was

ahead of the race leaders on the track, so the

finish had been staged for several minutes before

the glare of the MG’s headlights could be

seen glittering through the haze. It couldn’t

have worked better. With a flourish, the commentator

announced the arrival of the LMP2 winner. In solitary

splendour, and accompanied by an enormous cheer

from the crowd, the diminutive MG Lola EX264 wailed

its Judd-inspired battle-cry across the finish

line, Tommy pedalling the throttle into a crescendo

of defiance. Not only was he celebrating the finish

the team so much deserved; not just a podium,

but also that rare distinction, victory at Le

Mans. Mike Newton and Warren Hughes both climbed

high atop the pitwall to welcome home their car,

their feet swathed in the waving arms of a mass

of cheering and ecstatic team members, better

halves and sponsor’s guests. It was an enormously

emotional moment, and the relief that comes after

so many hours of strain and pressure was clear

for anyone to see.

The

final two hours of the race had produced some

of the most extraordinary motorsport likely to

be witnessed for some time. While motor racing

in America was making headlines for all the wrong

reasons, the greatest race of them all was demonstrating

just why Le Mans and legends go hand-in-hand.

Throughout the field, in every class and category,

there had been genuine competition and nail-biting

excitement. Nowhere was this more tangible than

in the RML garage, where triumph really had been

dragged kicking and screaming from the jaws of

apparent disaster.

One of the drivers suggested that the car itself

simply didn’t want to finish the race. At

every turn, no matter what hurdle the hard-working

team had ovecome, another obstacle would be thrown

in their faces. From the very first hour this

had been a rollercoaster race of despair and delight

– on the one hand, the frantic struggle

in the garage each time something went wrong,

and on the other, the sight of the MG EX264 and

one of its drivers blasting away up the pitlane

to begin another fight-back from ten laps down.

In

the end the RML MG Lola EX264 covered a total

of 305 laps on its way to winning LMP2, taking

24:05.45.284 hours to do so – the greatest

total time of any car in the race. The #36 Courage

C65 of Paul Belmondo Racing finished second on

300 laps, with the #37 sister car fourth on 294

laps. Fourth place fell to the #30 Kruse Courage

on 268 laps.

Back to

top

Conclusion

We

managed to get words out of the drivers after

the race, finding Warren sitting on the floor

in the driver’s rest room, elbows on knees

and hands clasped around his neck. We

managed to get words out of the drivers after

the race, finding Warren sitting on the floor

in the driver’s rest room, elbows on knees

and hands clasped around his neck.

“I have never seen a team of people work

so hard before, never,” he insisted, shaking

his head in disbelief. “Those boys just

wouldn’t give in. They’re the ones

who won this race, not us.” His voice, hoarse

from a flu-like bug, cannot hide his pride. “It’s

hard to live through that kind of experience,”

he continued. “It was just one thing after

another. It’s almost surreal. None of the

problems were related to the speed we were doing.

Even when we were forced into pushing, the things

that went wrong were nothing to do with that.

I was lucky though. My two triple stints, and

then that last double, were all relatively trouble-free.

Even during the night, the only glitch I had was

with the gearshift, and I had to switch to the

manual system.” This was actually quite

a frightening situation to be in. “The team

radioed a solution, and told me I had to switch

everything off going down the Mulsanne. All the

lights went out, everything!” He freewheeled

in the dark (at no mean speed!) before toggling

the appropriate controls and initiating the change

to manual. Thankfully, it worked.

“It’s

amazing to think that we didn’t touch one

car, didn’t have any unforced spins, and

we were quick all the way,” added Warren.

“The car was also the fastest [LMP2] in

the race. It wasn’t in qualifying, because

the others could turn up the boost on the turbo,

but they couldn’t do that in the race. Even

though we had the extra pace, after our initial

delays, overheating, and the gearbox, we needed

other people to have problems, which they did.

We were also very fortunate with Tommy that the

suspension failure didn’t happen anywhere

else, like Indianapolis or the Mulsanne, where

the speeds are so much quicker. When I saw that

on the screen I thought, well, that’s game

over. It was just one thing after another, but

credit again to the boys; they wouldn’t

accept that the car wasn’t going to finish.”

Tommy

shared the same gratitude for all the hard work

put in by the RML mechanics. Tommy

shared the same gratitude for all the hard work

put in by the RML mechanics.

“It’s all thanks to those guys. We’d

never have got there without them,” he said.

“They had a remarkable ability to deal with

everything that came along, and to do it quickly.

I admit, there were times in the middle when I

never thought we’d make it, but towards

the end I started thinking that perhaps there

was a chance. Even so, I was looking on P2 as

being the best we could probably hope for, and

I was more than prepared to be satisfied with

that. At least that would have secured us an entry

for next year.”

As

for the car’s third driver, well, the grin

never left Mike Newton’s face for what must

have been the best part of an hour. It was a pleasure

to see him so delighted, and to know that he had

played a significant role in his team’s

success. There have been certain people, those

who don’t look too closely at the figures,

perhaps, who have dismissed Mike as a driver,

but they’d be wrong to do so. Put anyone

alongside a pairing like Tommy and Warren, and

unless they were diehard professionals, they’d

all run the risk of looking slow. Mike never pretends

to be more than he is; an enthusiastic gentleman

driver, but perhaps that alone is where he falls

short. Weighed against those of others on the

track at the same time, professionals included,

his times compare very well indeed. If his best

race laps only occasionally dipped below four

minutes, they were consistent, and typically came

through several seconds quicker than those of

his immediate rivals in LMP2. He didn’t

shirk his duties either, and completed over five

and a half hours at the wheel; only two stints

less than Warren. He had every reason to look

fulfilled. As

for the car’s third driver, well, the grin

never left Mike Newton’s face for what must

have been the best part of an hour. It was a pleasure

to see him so delighted, and to know that he had

played a significant role in his team’s

success. There have been certain people, those

who don’t look too closely at the figures,

perhaps, who have dismissed Mike as a driver,

but they’d be wrong to do so. Put anyone

alongside a pairing like Tommy and Warren, and

unless they were diehard professionals, they’d

all run the risk of looking slow. Mike never pretends

to be more than he is; an enthusiastic gentleman

driver, but perhaps that alone is where he falls

short. Weighed against those of others on the

track at the same time, professionals included,

his times compare very well indeed. If his best

race laps only occasionally dipped below four

minutes, they were consistent, and typically came

through several seconds quicker than those of

his immediate rivals in LMP2. He didn’t

shirk his duties either, and completed over five

and a half hours at the wheel; only two stints

less than Warren. He had every reason to look

fulfilled.

In

every respect, this was a fantastic team effort

by everyone at RML, amply supported by Lola, Judd

and Michelin. It just seems such huge injustice

that the name of MG will appear in the annals

of Le Mans history two months too late, for here

is a story that deserves a bigger audience and

far greater recognition.

Back

to top

Marcus

Potts |